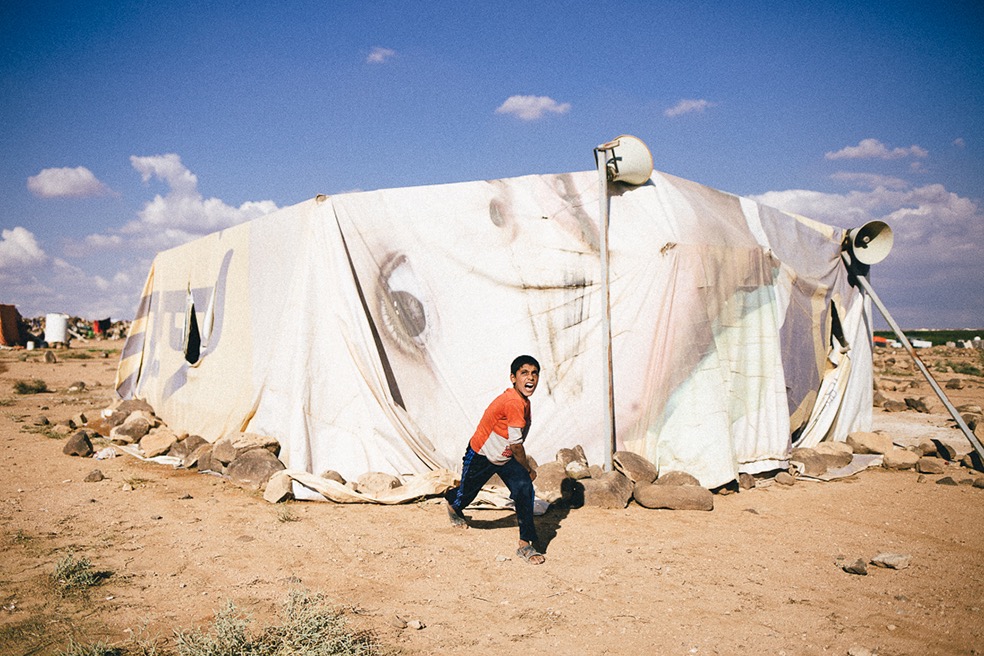

There is no end in sight to the war in Syria. Many Syrians have fled to Europe, where the number of asylum seekers soared during the month of October 2015. In Jordan, some refugees – including some of the most vulnerable – are living in makeshift tent villages rather than the official camps set up by the Jordanian government, without the latter’s authorisation and completely outside the law. As a result, they do not have access to international aid. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that they account for 20,000 out of the 633,000 in the country, and the vast majority are Bedouins.

More than being Syrian, Jordanian or Palestinian, Bedouins consider themselves to be first and foremost from the desert (Bedouin comes from the Arabic world meaning ‘desert dweller’), and their culture makes them very distinct from city dwellers. Their nomadic tradition drives them to move with the rhythm of the agricultural seasons. In Syria, where they represented between 5 and 10 per cent of the population, many had started to settle on their own farmland, abandoning, in part, their nomadic lifestyle. Most of them have lost everything to the war and any hope of returning has now been lost.

A Bedouin father recounts his experience of the Zaatari camp, managed by UNHCR in the north of Jordan: “We left after two weeks. I didn’t sleep a wink during all that time. I wasn’t able to trust them. The other refugees, non-Bedouins, would come into my tent all the time. I was afraid they would jump on my wife or my daughters.” For centuries, Bedouins have lived a separate life in the heart of the desert, limiting contact with other social groups. And although this lifestyle has changed somewhat with the modernisation of the nomadic way of life, it nonetheless remains firmly anchored in the Bedouin cultural ideal.

Proximity with other communities and forced integration, which they see as a violation of their privacy and, therefore, their honour and their freedom, makes life inside a refugee camp virtually impossible. Moreover, tensions with other groups hinder their access to the camp’s economic resources. Turquia’s family fled the war and reached the Zaatari camp in 2012. “We had problems with the other communities,” she explains. “We would be robbed and we didn’t have access to the supermarkets.”

Having now settled in the middle of the desert, Turquia says: “Here, at least, we are free.” Bedouins have always worked the land. Having lost their farms and cattle, they have returned to the cycle of moving with the seasons, working to make ends meet on Jordanian farms. They are a skilled, efficient and cheap source of labour. But they are not the only ones competing for work. The massive influx of Syrian refugees into Jordan has transformed this largely informal sector of the labour market, pushing down wages. There are those, driven by necessity, willing to accept an hourly rate of just 0.90 Jordanian dinars (around €1.20), less than half the amount earned by Jordanian, Pakistani or Egyptian farmworkers.

Amongst the many challenges facing the Bedouins, the most immediate is preparing for winter: protecting their dwellings from the rain and winds that can rip poorly-attached tarpaulins from the roofs of the tents, and insulating themselves against temperatures that drop to as low as 0ºC. Problems arising from conflicts with other agricultural workers also mean that the Bedouins sometimes have to pick up camp at a minute’s notice and find somewhere else, rebuilding everything from scratch.

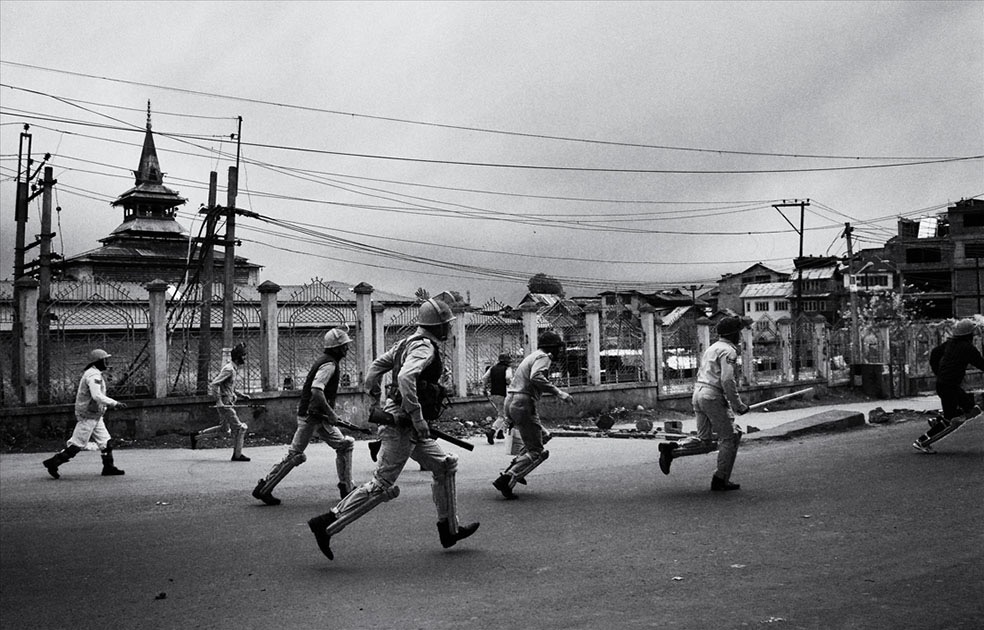

The Jordanian government takes a dim view of these informal settlements being set up around the country and would rather the refugees were kept within the confines of the official camps. Its main motive is security. But public opinion is also a key driver: Jordan is struggling with an unemployment rate of 12 per cent and the sectors in which the Bedouins work are amongst the hardest hit.

In June 2014, Bedouins were evacuated from five settlements in the Amman region and moved by force into the official Azraq refugee camp. It was not long, however, before many of them moved back to the desert. In the summer of 2014, a UNICEF report had already pointed to the Bedouins as being the most vulnerable community in the Syrian crisis. Aid workers have also been sounding the alert for some time. And the onset of winter will likely worsen the lot of these marginalised people, especially given that the funds allocated to help them have been blocked.

According to an NGO officer working with Bedouins, who wishes to remain anonymous: “Jordan is blocking the funds, to encourage Bedouins to return to the camps. The UNHCR has to maintain good relations with the Jordanian government, so the matter is not being sorted out.”

“In the meantime, the situation is getting a little worse every day.”

Website: tien-tran.com