Says Sebastián: In the summer of 2019 I set out on a cargo ferry from Punta Arenas to Wulla, the name that the Yagan people gave to Navarino Island prior to the European expeditions of the first half of the 19th century.

It brought to mind the imaginary trips I made looking at the maps of the Turistel ’88. The tour guide was stored in my father’s nightstand drawer. At that time I was six years old and I was travelling from Santiago to Puerto Williams following the path with my eyes. When I arrived at Villa O’Higgins, the red or black lines (depending on whether it was motorway or single carriageway) were replaced by the broken blue lines of ferries. After having to retake a black line through Argentina, my eyes managed to reach Uspushwea, the Yagan name of Puerto Williams. So I travelled, almost always to the same place, for several weekend mornings from my parents’ bed when they had already risen.

As an adult, my interest in the island has grown. I start reading its story; the Yagan people and their more than 6,000 years of touring the island and the canals south of the Beagle, European geographical explorations, the abduction of Jeremy Button, religious missions, human zoos, diseases, exclusion, confinement, and finally, the extermination of ancestral culture. The story horrifies me. Nearly two centuries have passed since then, and I wonder: Who inhabits this island today? What is your current identity?

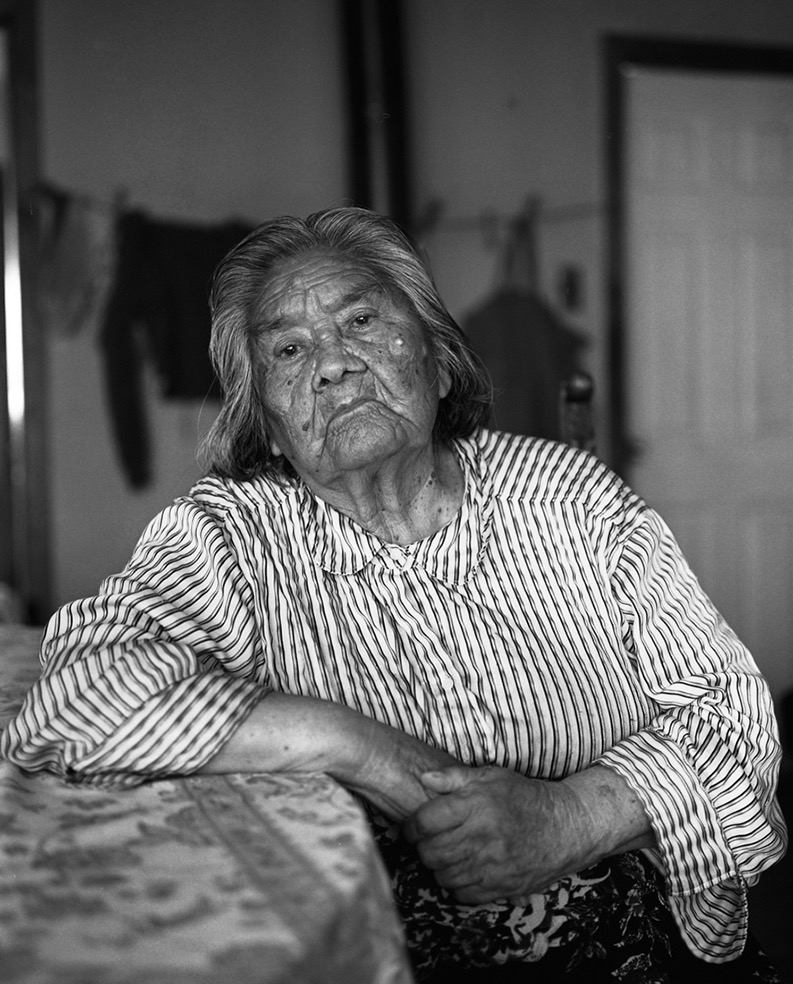

After almost two days of intense winds and strong swells, I arrive at the southernmost city in the world, Puerto Williams. The weather is extreme, nature is wild. Only the calendar reminds me that it is summer. I walk in search of its people, its inhabitants. I visit Cristina Calderón, the only fluent speaker of the Yagan, recognised as the Living Human Treasure. She receives me at her home in Villa Ukika. The door of the house is open, the fireplace is lit, the windows are fogged. Grandma Cristina, as they call her affectionately on the island, is of few words but accurate. Her son Eugenio tells me of the little respect of some when they visit her, the morbidity of human zoos seems to continue in some tourists. After three visits I can portray her. In Cristina’s eyes I see more than 6,000 years of history.

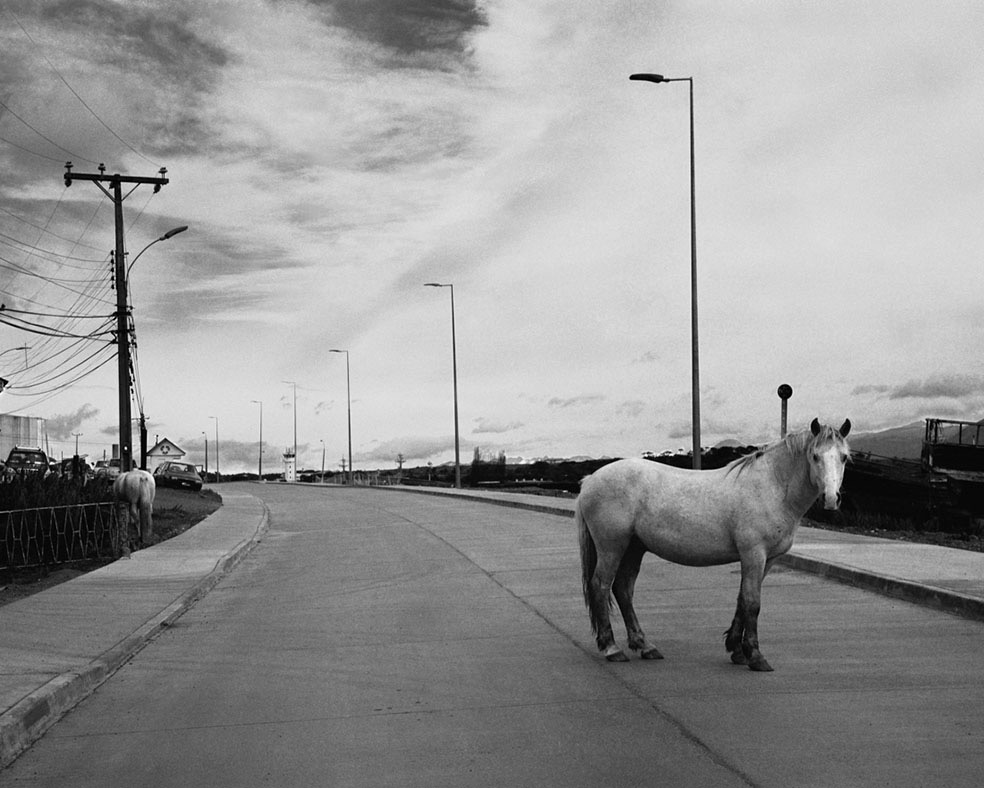

I spend days walking through the streets of the city, dogs and wild horses accompany me. I enter the bar Dientes de Navarino where Yamila works. She receives me with distrust, but allows me to stay with her the next day to make a portrait. A Colombian from the city of Cali speaks to me behind the restaurant bar, telling me how she arrived in Chile in 2012, and from Santiago travelled directly to Punta Arenas. She only needed two days to receive a job offer from the newspaper El Pingüino in Puerto Williams. She was the first, and for a long time, the only Afro-descendant woman who lived there.

I wander the island, visit an old Yagan site where there is only one cemetery left. The weather is inhospitable. From the stern of the historic ship Micalbi I can see the snowy peaks of the Dientes de Navarino.

In a small local minibus I arrive in Puerto Navarino. Cape Jarpa and his family live here and are its only inhabitants. He was posted for a year to live in this hamlet about 55 km west of Puerto Williams. Moisés is the only employee in the office where he works. He has the responsibility of verifying the entry of people from Ushuaia through from the only port’s pier. The phone signal is very weak. Their children go to school in their own home where Stephanie, their mother, teaches them.

Puerto Toro faces Picton Island. A sign proudly announces it to be the southernmost town in the world. Thirty-six people inhabit it. The same ferry that brought me to the island comes once a month to bring supplies to the town. There is no land road that connects it to Puerto Williams. I take a portrait of José Catrín, son of the oldest settlers in the village. His origins, like those of many at Navarino Island, are on the island of Chiloé. While José stores the community gas containers brought from the ferry, he tells me that he still has memories of the Beagle conflict. He says you can still find trenches around the place.

Days pass, the weather becomes more extreme, fewer and fewer tourists. Next to the anthropological museum I find the Stirling house. The museum’s archaeologist explains to me how this was the first western dwelling to arrive in Tierra del Fuego. It was brought prefabricated from the port of Bristol in England by an Anglican mission.

I wait for the ferry back to Punta Arenas. I reflect on the multiple identities that inhabit the island today, and how the descendants of the Yagan people make efforts to recover and maintain the continuity of their ancestral language and identity. They know they have a very high risk of disappearing. The community resists it.

Isla Navarino is a photographic documentary project carried out in an analogue medium format during the beginning of 2019. From a personal point of view, the work aims to meet its inhabitants, documenting the testimonies and experiences of different cultural identities that are developing today in what is called the World Biosphere Reserve.

Sebastián Thomas was born in Santiago of Chile in 1982. Currently he is based in Bristol, United Kingdom. He studied Professional Audiovisual Communication at the DuocUC institute, and then studied a degree in Aesthetics and Photographic Practice at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. He also made Analog Photography workshops with photographer Luis Poirot. Later he participated in the Documentary Film workshop given by the International Film and Television School of San Antonio de los Baños in Cuba.

His works currently are in analogue black and white photography, in medium format and 35mm. It focuses on people and daily life, trying to find in them the poetic and invisible. Sebastián has shown his work in solo exhibitions in Chile and group exhibitions in Argentina, Peru, Uruguay, Brazil, Germany and the UK. He is currently working on projects between the UK, Chile and Spain.

Website: sebastianthomas.cl