Fabian Muir is an Australian documentary and fine art photographer, and occasional writer, currently based in Sydney. The principal motivation behind his projects and practice is a focus on humanist issues combined with strong visual storytelling.

In addition to extensive experience in documenting the countries and de facto republics of the former Soviet Union, he has recently completed a two-year project on the DPRK (North Korea). His work on North Korea was selected as a documentary finalist in the inaugural Magnum Photography Awards 2016 and has been honoured as finalist in the 2017 FotoEvidence Book Award. ‘Shades of Leisure in North Korea’ was selected as finalist for the 2017 ZEISS Photography Award.

He has had major solo and group exhibitions in galleries and festivals around the world and his work has been acquired by significant collections. Outlets in which work and interviews have appeared include The Guardian, The Atlantic, VICE, BBC World TV, LensCulture, SPIEGEL, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, BBC Asia, BBC Online, FotoEvidence, Vogue Entertaining + Travel, Sueddeutsche Zeitung, BuzzFeed, Leica Magazine, ZEISS Lenspire, France Culture (Radio France), The Sydney Morning Herald, Fotoblogia (Poland), LIFO, Bird in Flight, FAHRENHEITº Magazine, MindFood Magazine, Ampersand Magazine, Studio Magazine, Bios Monthly (Taiwan), La Repubblica, Lenta.ru, The Age, Black + White Magazine, Konbini, Capture Magazine, Photojournalink, Street Photography Magazine and Feature Shoot. His short film Holiday in Abkhazia won the award for best screenplay at the Strasbourg International Film Festival in 2009. He is represented by Michael Reid Gallery in Sydney and Berlin.

Website: fabianmuir.com

How did you get interested in photography? Do you have an educational artistic background?

I have no formal training in photography and actually studied law, but I grew up in a family working in creative fields (film, television, theatre and opera) and cameras were always lying around the house while photographic references were ever-present. This drew me to photography at an early age, even if I never imagined at that point that I would end up working in the field professionally.

For a long time my own focus lay more in writing, then over time I began to understand how wonderfully images and the written word can complement each other, as well as how certain images could express things in a more subtle, visceral or immediate way than text. I first realised that my own photography had some actual potential when outlets began to run images I had taken to accompany pieces I was writing. Later the shock of my mother’s rather early death caused a kind of writer’s block and I shifted over entirely to photography, which has been my ‘dominant hand’ ever since.

Where do you get your creative inspiration from? Is there any other artist or photographer who inspired your art?

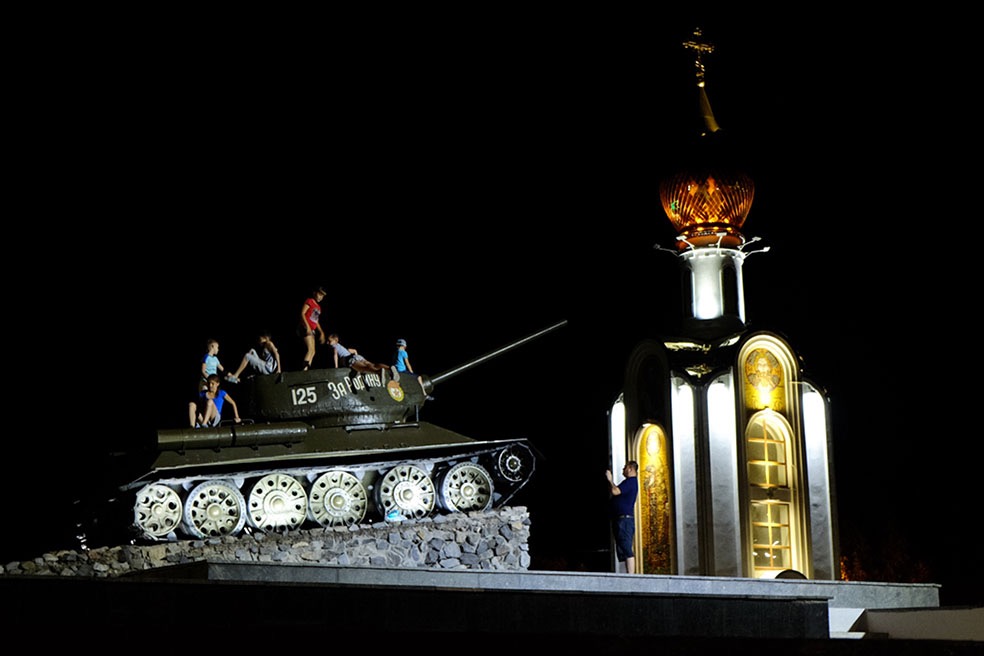

Given my background, a lot of my photography is informed by literature, theatre, film and current affairs, and I think this leads me to seek to create images that suggest stories. I often strive for images that try to be less obvious and open themselves to the viewer over time, in much the same way a character in a novel or film invariably turns out to be someone quite different from the assumptions one makes about them at the beginning.

Broadly speaking, I feel that Magnum photographers have most inspired my approaches to photography and it’s often their work that seems to resonate with me most strongly for their ability to observe something meaningful in unexpected ways and places. While there is also merit in tackling humanist issues by applying ‘straight’, newswire-type practices, this is not for me. I find there is an important place for irony, humour, subtext or art in images. For this reason it has usually been artists and photographers whose images pose questions and who offer more layered elements along these lines that most attract me. Then there are other photographers like Chang Chao-Tang, who seem to work in a space that defies any kind of definition, but whose images profoundly challenge the viewer and completely mesmerise me.

How much preparation do you put into taking a photograph or series of photographs? Do you have any preferences regarding cameras and format?

A great deal of research and planning goes into the work beforehand. I spend a lot of time identifying potential themes and locations, which is coupled with reading up on the literature and background articles, viewing relevant documentaries and so on. This is critical to giving me a plan and a sense of direction, although I always remain open to the possibility that things might turn out differently when I’m on the ground with the camera in my hand and see things with my own two eyes.

Overall I’m usually in two minds about looking too closely at other people’s work on similar subject matter beforehand, since this will inevitably influence my own images in some way, which is more distracting than helpful. As a rule I find I can work more effectively if I can go in with a clear mind and without the noise of other visual references affecting the way I shoot. However the photographer who says he/she is completely free of influences is either deluded or lying!

In terms of gear, I try to keep things as classic and lightweight as possible. For documentary work especially, I’ll walk around with a single mirrorless body with a 28mm or 35mm prime or a short zoom attached. Even before I moved to digital, all my photography was done with a Contax and a couple of prime lenses. I do everything on manual settings, which usually means there is relatively little work to be done in post.

Given the technology on offer I can understand why certain photographers like to haul around DSLRs, but I don’t think I could work as effectively that way, plus I find considered, ‘old school’ methods provide much deeper satisfaction when one captures a good picture as opposed to spraying out images as 16 FPS with the camera doing everything for you, at which point you may as well shoot a video.

Can you talk a bit about your approach to the work? What did you want your images to capture?

I mentioned earlier the possibility of things turning out differently from what I’m expecting once I’m on the ground, and the North Korean work is a good example of this. By and large the material we see on North Korea in the media presents a dominant narrative of military parades, the regime, bombs and food shortages, since there appears to be a disinclination or inability to turn the pen or lens to something as simple as ‘daily life’ or ‘normal’ people in that country.

Needless to say, most of my initial research also led to these kinds of narratives, so prior to my first visit to North Korea I was fully expecting to find much of the same once I was there. It was only during my first trip that I discovered that there are many other stories in the DPRK that tend not to attract attention. These interested me far more than producing work that simply echoed material we have already seen a hundred times before.

So in this sense I wanted the images to capture a North Korea that most viewers don’t typically realise exists, and it required many visits to collect the material. The work is not aimed at refuting what people do already know about the country, but it’s important that this be supplemented by an awareness that there are many more human strands to life in North Korea that escape mainstream attention and that our understanding of the place and its people has frequently been too simplistic. Consequently, after my first visit, I shifted my research for subsequent trips to focus on these lesser-seen sides of life, both in and outside Pyongyang, and this project is the end result.

Tell our readers more about your award-winning project „Shades of Leisure in North Korea”.

Both the project itself and subsequent rolling out the images have been fascinating experiences.

North Korea as a country is a very complex proposition and it is a difficult environment in which to shoot, not so much because people interfere with your pictures (in fact this virtually never happened) but due to the constraints on one’s freedom of movement, specifically the guides/minders who accompany you almost constantly.

By definition this is going to limit what you can discover there, so you have to accept it and learn to operate within these limitations, and even how to make them work for you, since the guides can actually facilitate a great deal and even open unexpected doors. While I understand that there are many sides to North Korea to which a foreigner will never gain access, overall I was quite satisfied with the access I was given and the material I could put together, especially in locations away from Pyongyang (many photographers seem to think that visiting the capital means you have seen the entire country, which is ridiculous). It’s worth pointing out that my images were never vetted by authorities, be it at various borders or while in the country.

As mentioned, rolling the images out has also been an interesting experience. In some other interviews I’ve referred to Thomas Hoepker’s work in the GDR or Cartier-Bresson in the USSR, both of whom brought human faces to places that previously had none; I have tried to do something similar with North Korea, and it’s disappointing for me when some people struggle to see that.

European publications have been supportive of the work, but in the US it has often been quite difficult, since there are certain editors who — so it seems — do not trust the images and feel I have either fallen for elaborate scenarios staged entirely for my benefit or that I might even be on the North Korean payroll. Unfortunately I think the preconception of the unsmiling, militant North Korean is deeply entrenched in their minds to the exclusion of all else, meaning that anything deviating from this can arouse suspicion.

In many ways this has been a warning that stories that question preconceptions can be a much harder ‘sell’ than those that subscribe to the easy and established narratives; it would have been a far simpler route — though less honest — for me to offer a series consisting entirely of grim pictures that satisfied such editorial expectations.

I must confess I have at times been quite frustrated by these people who apparently believe they know everything about North Korea from their office, without having actually been there themselves. It was really only after the work began to pick up awards that some of them became more open to it and in this sense I am of course also very grateful for the PhotogrVphy Grant.

When all is said and done, however, it has been one of the most challenging and fulfilling projects I have ever undertaken.

Where is your photography going? What are you currently working on and do you have any photographic plans for future?

I pursue two strands in photography, specifically documentary work and what you might call politicised fine art, most recently on refugees and immigration. The documentary practice is invariably long-form since I think it’s generally difficult to produce anything meaningful in a couple of weeks — I am currently focused on Iran as well as an ongoing survey of the former Soviet Union that has already taken years. I will also be working with FotoEvidence in 2018 on a book of the North Korean work, while I’m also currently in the early stages of conceptualising an art series that relates to the environment.

What are your three favourite photography books?

Dream Life by Trent Parke

Satellites by Jonas Bendiksen

The Images of Chang Chao-Tang, 1959-2013

What do you do besides photography?

I take a huge interest in almost anything arts-related, be it visual or plastic arts, film or music. When in my home town of Sydney, I love going down to Bondi Beach to swim, clear my head and feel everything fall away. I also enjoy cricket, which is probably something only cricket fans can understand! Above all, our first child is coming next year, so that is clearly the most exciting project imaginable.

Website: fabianmuir.com