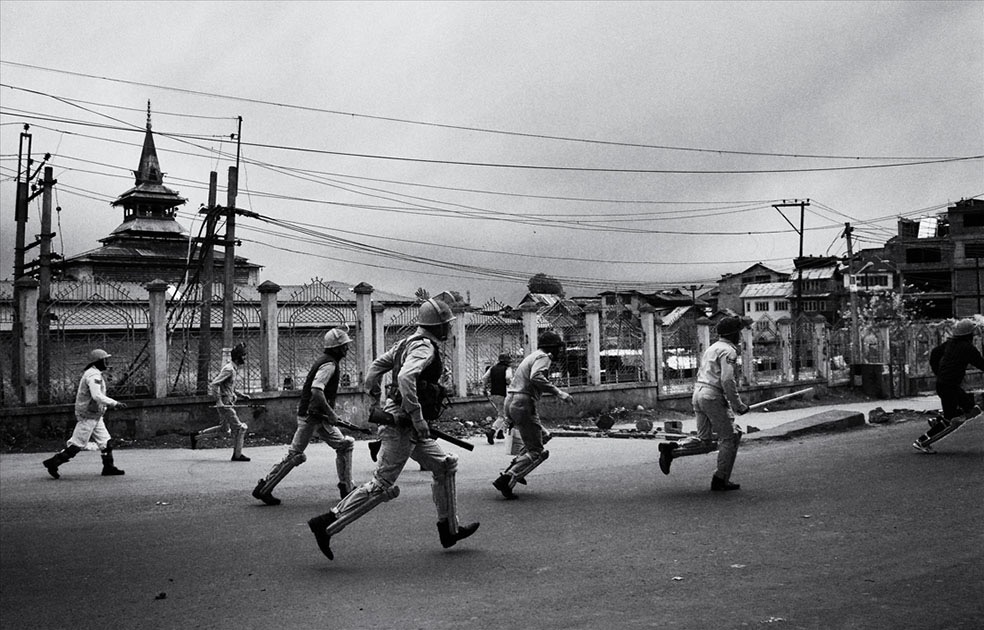

The valley of Kashmir, a territory disputed by India and Pakistan since 1947, is one of the most militarized zones in the world. In 2010 the Indian government provided the security forces deployed in the state of Jammu and Kashmir with a new weapon. Shotgun shells filled with hundreds of small lead pellets are since then used to keep urban protests under control. Defined as a “non-lethal” weapon, pellet guns should be aimed at the lower part of the body.

On 8 July 2016 guerrilla group Hizbul-e-Mujahideen’s young commander Burhan Wani was killed in an encounter by the Indian army. Popular especially among the youth thanks to his use of social networks to spread his message, Wani’s martyrdom was the sparkle that lighted up the entire valley. The government imposed a four-month-long curfew on the local population, while separatist leaders called for a continuous strike.

Hundreds of young boys filled the streets of Kashmir protesting against the “Indian occupation”, throwing stones against the army and the Kashmiri police. Security forces, since July 2016, responded using pellet guns extensively. According to a UN report released in 2018, the new weapon is responsible for blinding around 1000 people and killing dozens.

Many of the victims were not involved in the clashes with security forces. Those who were hit during the protests tend to avoid speaking about it openly, fearing retaliation by the police. For youngsters left with one eye reading has become too painful, thus forcing them to abandon their studies, giving up the chance of pursuing higher education. Men left blind, the only breadwinner in the family, are unable to work and provide for their beloved ones.

Carrying dozens of pellets in their bodies, victims face unknown long term health consequences. Left partially or totally blind, victims speak of the darkness descended upon their lives. The only things left to see are the faint shadows that surround them.

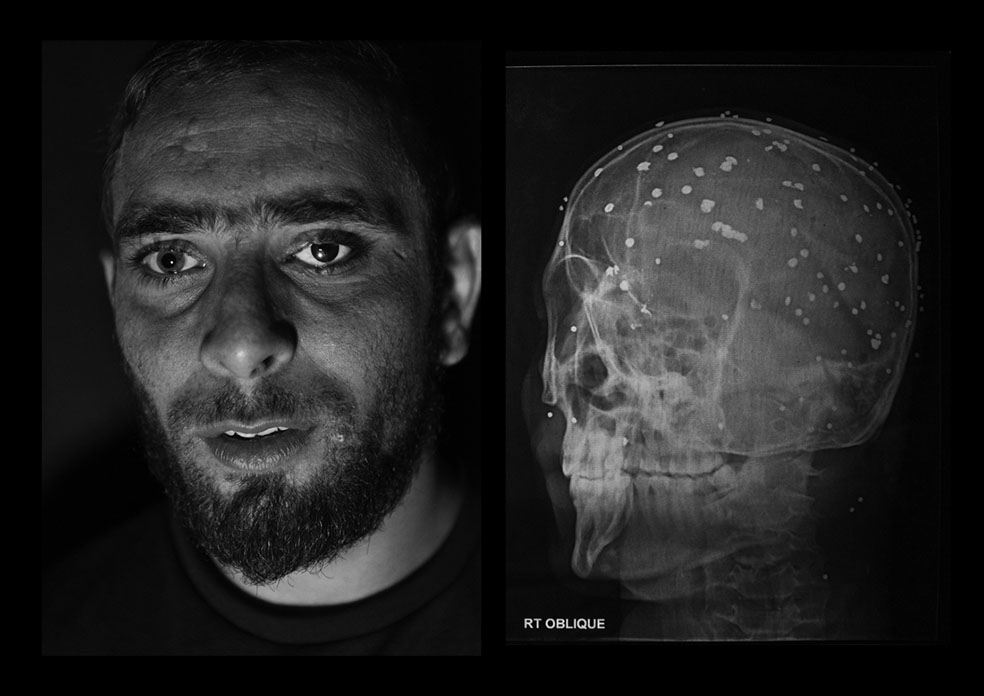

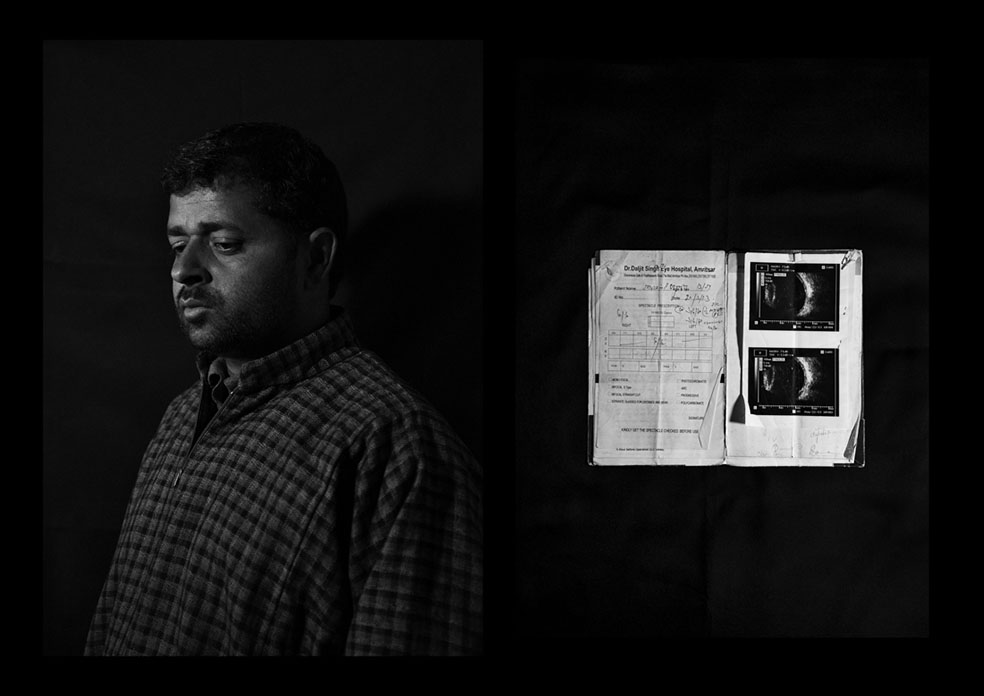

Amir is the first pellet victim of Kashmir, he received hundreds of iron balls on his body.

Camillo Pasquarelli was born in Rome in 1988. Only after completing his studies in political science and anthropology, in 2015 he decided to devote himself entirely to photography. Nowadays, is mostly interested in personal and long-term projects and deals with documentary photography trough the combination of the anthropological approach and the photographic medium.

Since 2015 he is working on a visual project about the valley of Kashmir, India, exploring the notion and the experience of conflict, memory, religion and political aspirations. In 2017 he received one of the Alexia Foundation Student Grant to keep working on “The endless winter of Kashmir”.

His works have been published in Der Spiegel, Mashable, Il Reportage, Gazeta Wyborcza, Il Manifesto, Left, The Post Internazionale, East. He was part of exhibition in Moscow, Rome, Getxo, Tbilisi, Bologna, Hyderabad.

Website: camillopasquarelli.com

Arif received 2 pellets on the right eye and completely lost the vision.

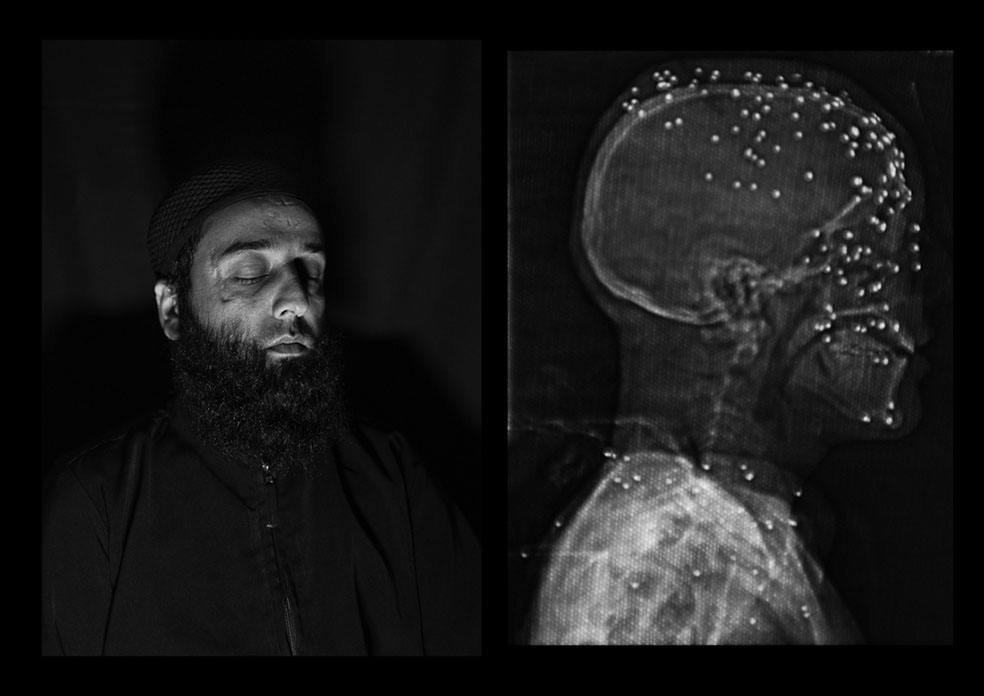

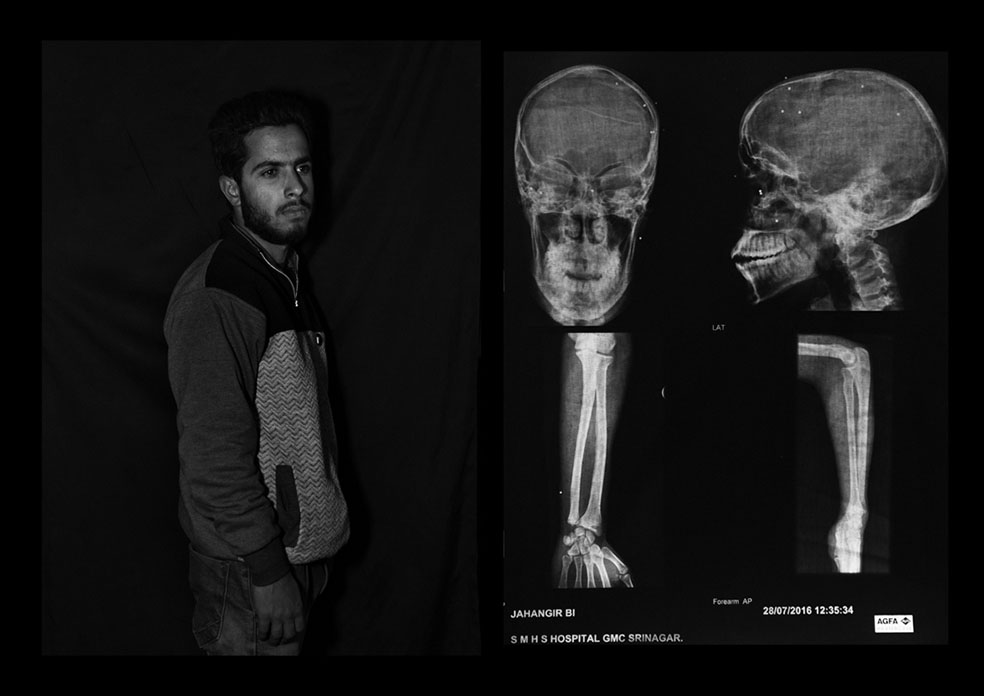

On the 2nd august 2016 he has been injured during the clashes. He was passing by that aerea but the police targeted him. He received 93 pellets all over the body and 2 on the left eye. After three failed surgeries he is now able to see only shadows wich is the reason why he decide to end his studying.

Shakeela received dozens of pellets on the chest, 1 on the left eye and 2 in the right one. The pellets have been shot from a very short distance and they have gone beyond the retina leaving her only 10% of the vision.

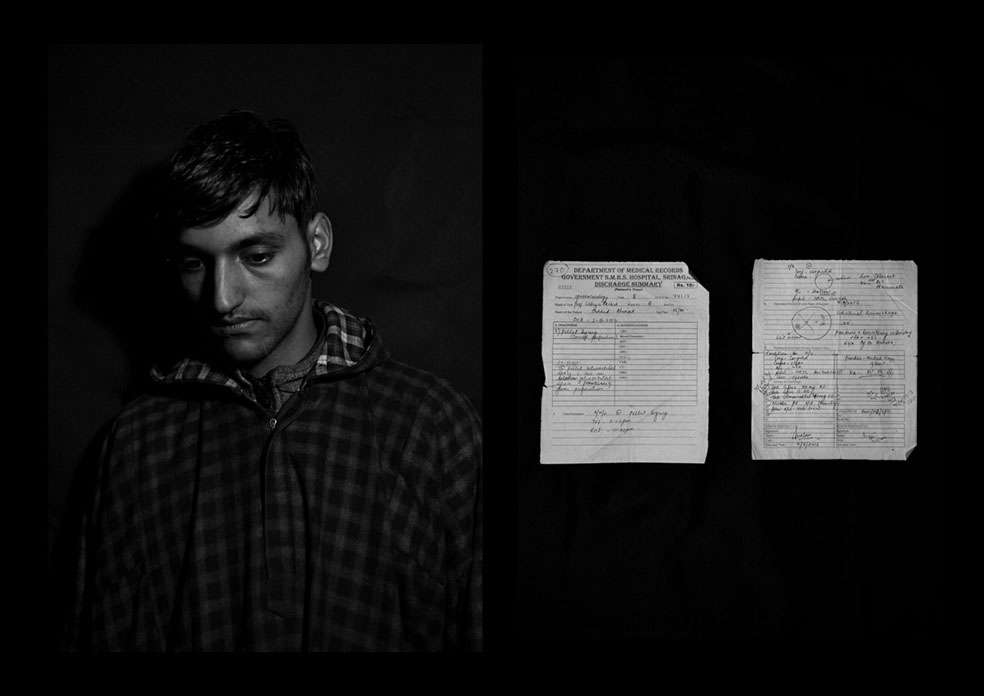

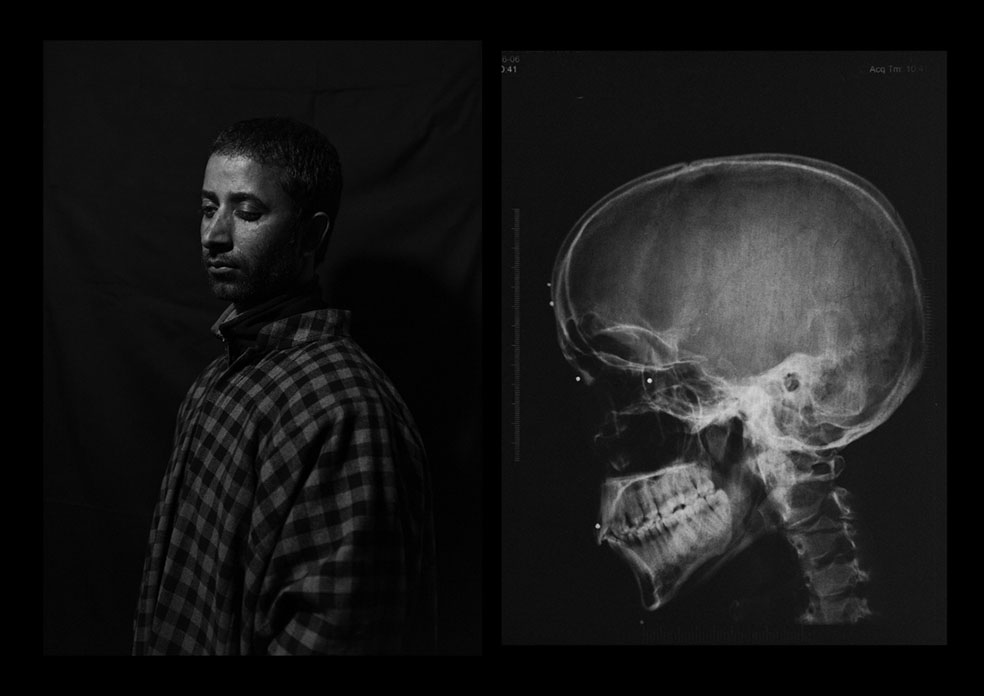

“I was walking to a shop and there was no protest around but suddently a Central Reserve Police Force vehicle arrived and opened fire. I screamed for the pain and some people came and took me to the hospital. I just have bought a new autorickshaw – local taxi -selling a piece of land, but now i can’t use it. With it i should have substain my family instead of being completely dipendent on them as i am now”. Firdous received 6 pellets in his left eye. He completely lost his right eye hitten by 7 pellets.

Faiz received 20 pellets out if it 2 damaged the right eye and now he claimed to be able to see only shadows.

Habid received 2 pellets in the right eye and his vision is baerly 1%.