One death is a tragedy, one million is a statistic. – Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin

Wars, states of emergency and continuing repression are immense breeding places for the pogroms against the people sacrificed in order to achieve political or economic goals. Terror that serves the ideology is a phenomenon imprinted in collective memory and is nowadays perceived as a consequence of so called human nature according to which, people are prone to domination, power tripping and competitiveness. It follows, that a human being is in fact an essentially evil and dangerous creature. The history of humankind, charged with bloody testimonies and traumatic memories, leads to identical conclusions. Parallel to the development of humanistic studies, science and technology the modern age has also encouraged the development of methods of elimination of adverse elements in society. Dogmatic ideologies haven’t (yet) lost their potentiality.

Throughout history mass killings and organised terror were taking place under different slogans and flags, though WWII has led to catastrophe of unimagined proportions: total war, global instability and the most extreme and brutal forms of disabling of potential opponents. The Nazi state developed the idea of repressive cleaning of disruptive individuals within society into a flawlessly functioning industry. However, concentration camps were not a novelty at that time. They were already conceived in the 19th century for the purpose of eliminating war prisoners from both sides of the American civil war (1861-1865) and refined during the Second Boer War in South Africa (1899-1902) when British military forces imprisoned tens of thousands of civilians who might have provided help to the rebels. A concentration camp is thus a place for extrajudicial imprisonment which a government uses to keep people who are either against that government or who it thinks are too dangerous to remain free.

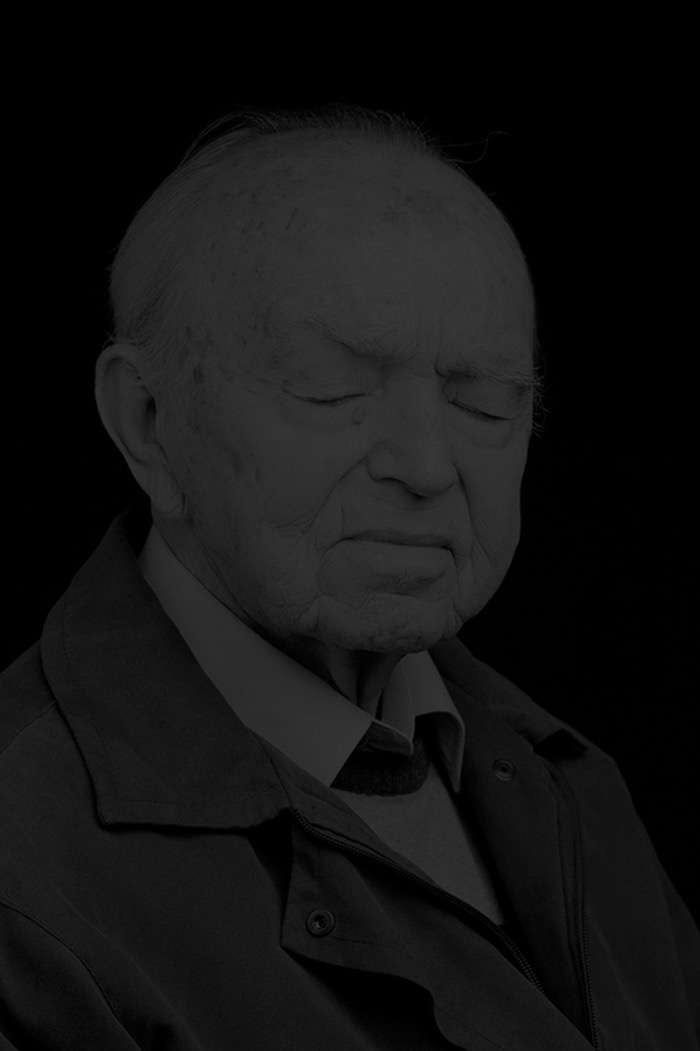

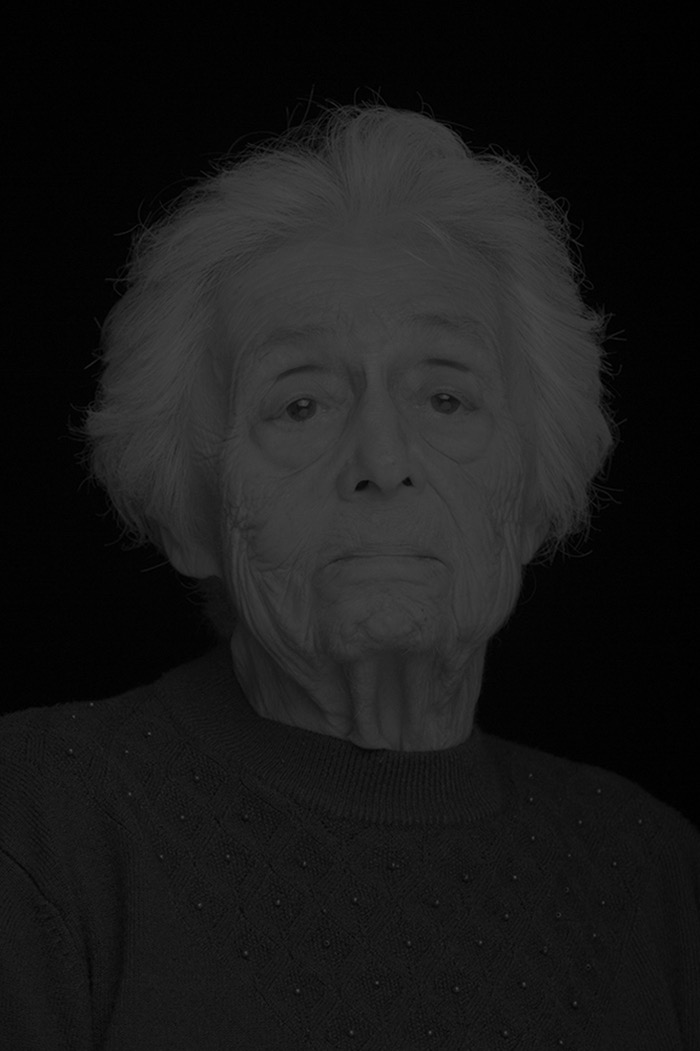

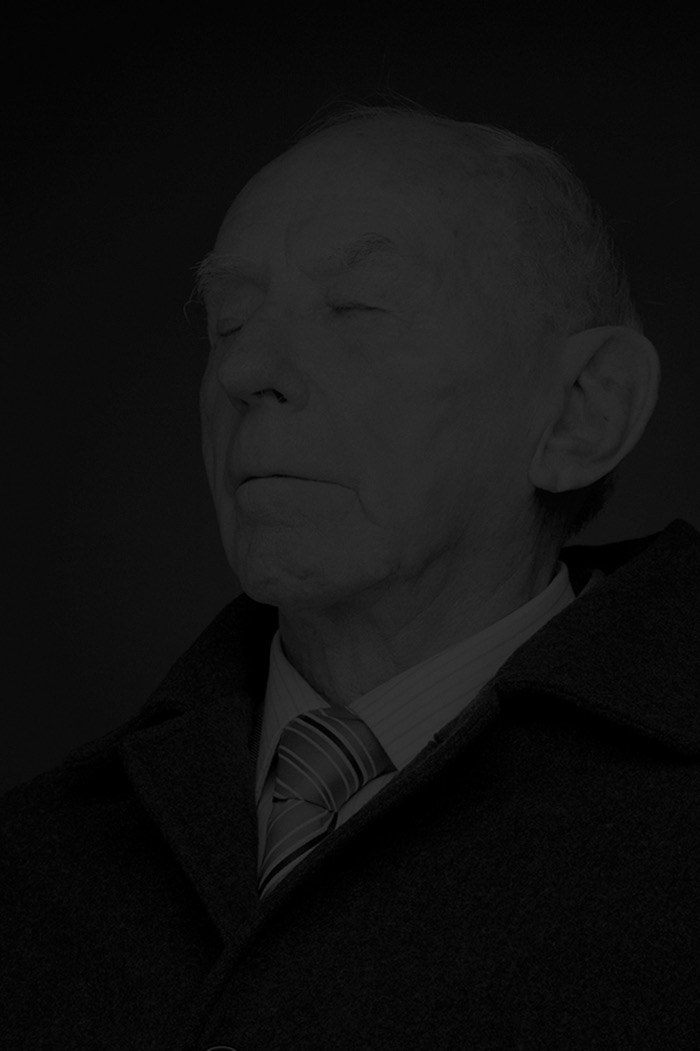

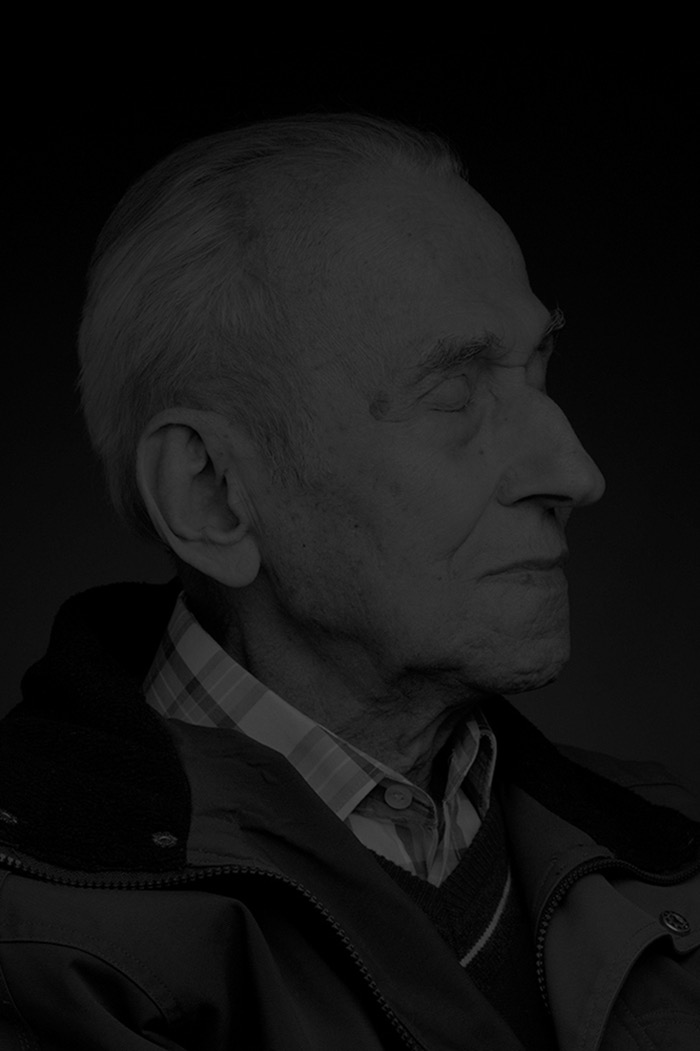

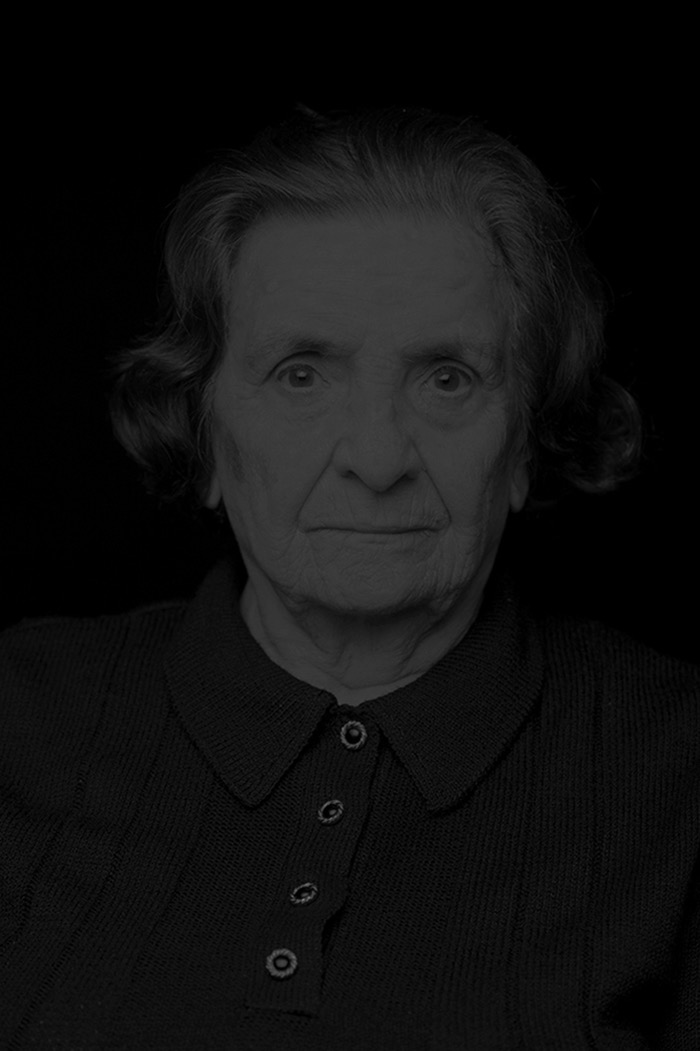

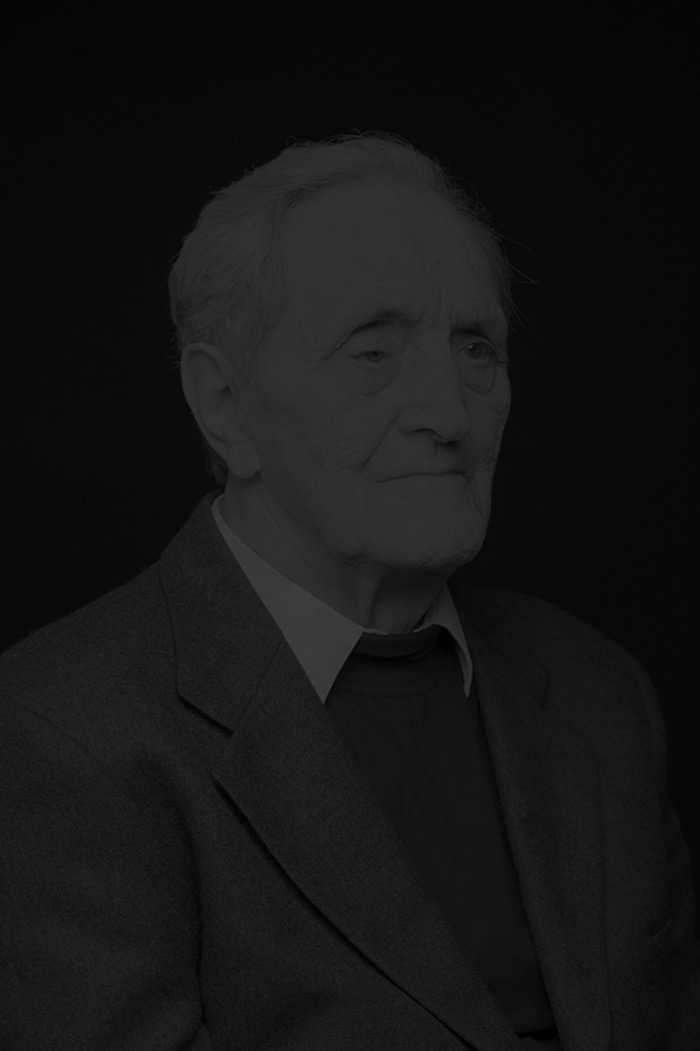

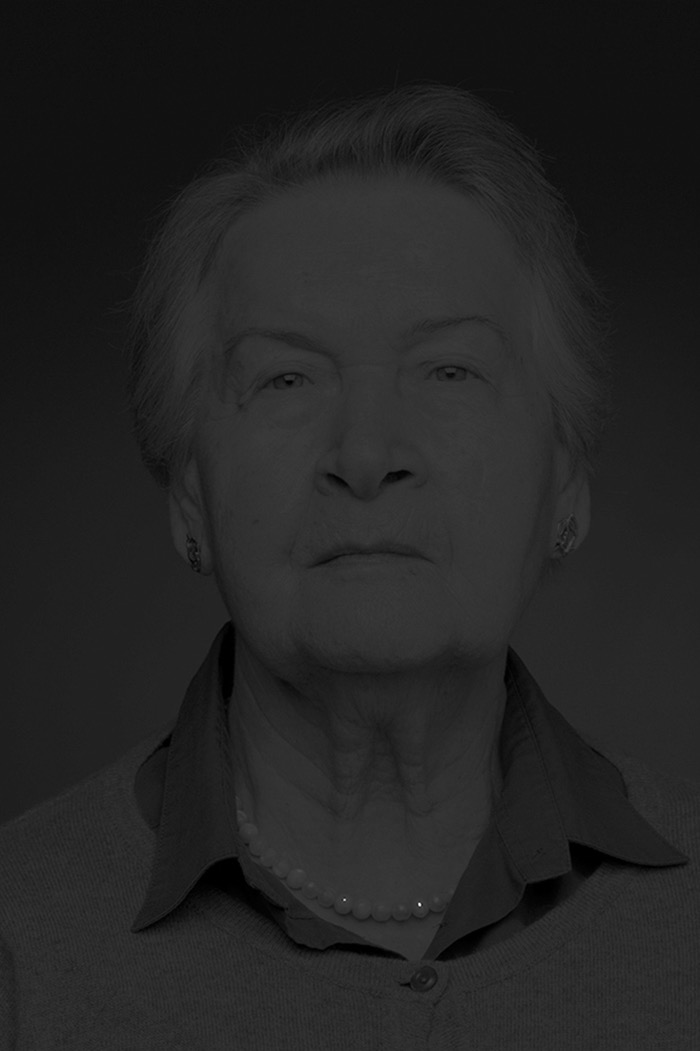

Goran Bertok’s recent series of photographs is devoted to the protagonists who – either as victims of opposition and rebellion or as collateral damage of Third Reich’s demographic policy – experienced the horrors of Nazi concentration camps and survived; however, these places where human life is worth almost nothing have left indelible marks on their victims. The portraits of former inmates however don’t show explicit signs of violence visible on their bodies, these are instead ambivalent images of the elderly who have already stared into the eyes of death many years ago in front of the spectator. They are reminders of these tragic events for which the entire world has vowed they should never happen again. However, historical memory is indeed very short-lived. After 1945 the repressive apparatus – of both Western or Eastern powers – didn’t essentially soften; innumerable war prisoners and political dissidents were thus taken to forced labour camps in Siberia by Soviets while the American Army locked up and starved to death around one million Wehrmacht soldiers in improvised camps.

Reasons behind such violence are often very complex and deeply rooted in the socio-political and economic situation of a certain place and time when people’s plights are often transferred onto the Other. In her essay ‘On Violence’ Hannah Arendt stated that “power comes from the collective will and does not need violence to achieve any of its goals, since voluntary compliance takes its place. As governments start losing their legitimacy, violence becomes an artificial means toward the same end and is therefore, found only in the absence of power.” If powerlessness of this kind lead to the terror of incalculable proportions, only the conscious power of the people could prevent it. After WWII Europe tried to maintain an awareness of the inhumanity of nationally and racially intolerant totalitarian ideologies and thus created the enormous physical and mental infrastructure of memory that – in order to avoid the recurrence of ideological violence – demands empathy for millions of innocent victims – the ones who died and the ones who survived.

Goran Bertok – born in 1963 in Koper, Slovenia. In 1989 graduated in Journalism at the Faculty of Sociology, Political Sciences and Journalism in Ljubljana; enlisted as a soldier into the Yougoslav National Army; after a month dismissed from the service with a diagnosis of a »psychopatic personality«.

Website: bertok.si